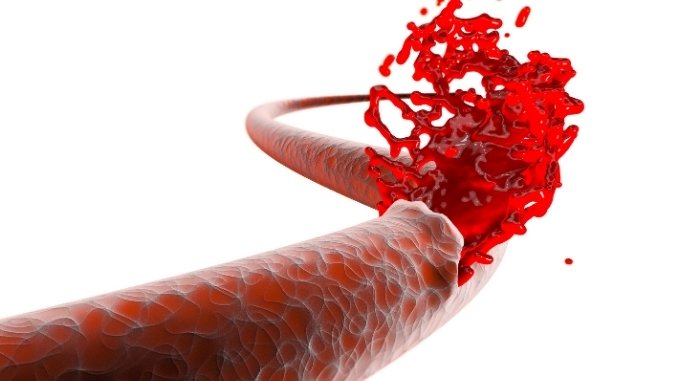

Researcher develops fast, portable, and pocket-friendly diagnostic for rapid blood loss

Melbourne (Australia) [India]: After conducting research, engineers have recently developed a fast, portable, and pocket-friendly diagnostic that can help deliver urgent treatment to people at risk of dying from rapid blood loss.

Findings were published in the prestigious journal, ACS Sensors. In a world-first outcome that could save more than two million lives globally each year, researchers at Monash University in Australia have developed a diagnostic using a glass slide, Teflon film, and a piece of paper that can test for levels of fibrinogen concentration in blood in less than four minutes.

Fibrinogen is a protein found in the blood that is needed for clotting. When a patient experiences a traumatic injury, such as a serious car accident, or major surgery and childbirth complications, fibrinogen is required in their blood to prevent major haemorrhaging and death from blood loss.

This new development by researchers at Monash University’s Department of Chemical Engineering and BioPRIA (Bioresource Processing Institute of Australia), in collaboration with Haemokinesis, removes the need for centralised hospital equipment to detect, monitor, and treat fibrinogen levels – something never achieved until now.

Additionally, this diagnostic can be upscaled into a point-of-care tool and placed in ambulances and other first responder vehicles, in regional and remote locations, and in GP clinics. It takes just four minutes to complete.

Professor Gil Garnier, Director of BioPRIA, said this diagnostic will allow emergency doctors and paramedics to quickly and accurately diagnose low levels of fibrinogen in patients, giving them faster access to life-saving treatment to stop critical bleeding.

“When a patient is bleeding heavily and has received several blood transfusions, their levels of fibrinogen drop. Even after dozens of transfusions, patients keep bleeding. What they need is an injection of fibrinogen. However, if patients receive too much fibrinogen, they can also die,” Professor Garnier said.

“There are more than 60 tests that can measure fibrinogen concentration. However, these tests require importable machinery on hospital tabletops to use. This means that critical time has to be spent transporting heavily bleeding patients to a hospital – before they even undergo a 30-minute diagnosis,” added Garnier.

PhD candidate in the Department of Chemical Engineering and research co-author, Marek Bialkower, said the implications for this diagnostic are significant.

The diagnostic can work with a variety of blood conditions. Hypofibrinogenemia (insufficient fibrinogen to enable effective clotting) in critical bleeding is common. More than 20 per cent of major trauma patients have hyperfibrinogenemia.

Dr Clare Manderson, Research Fellow in the Monash Department of Chemical Engineering and co-author of the study, said the early diagnosis of hypofibrinogenemia could stop bleeding in these patients and save their lives.

“The development of the world’s first handheld fibrinogen diagnostic is a game-changer for the millions of people who die each year from critical blood loss,” Dr Manderson said.